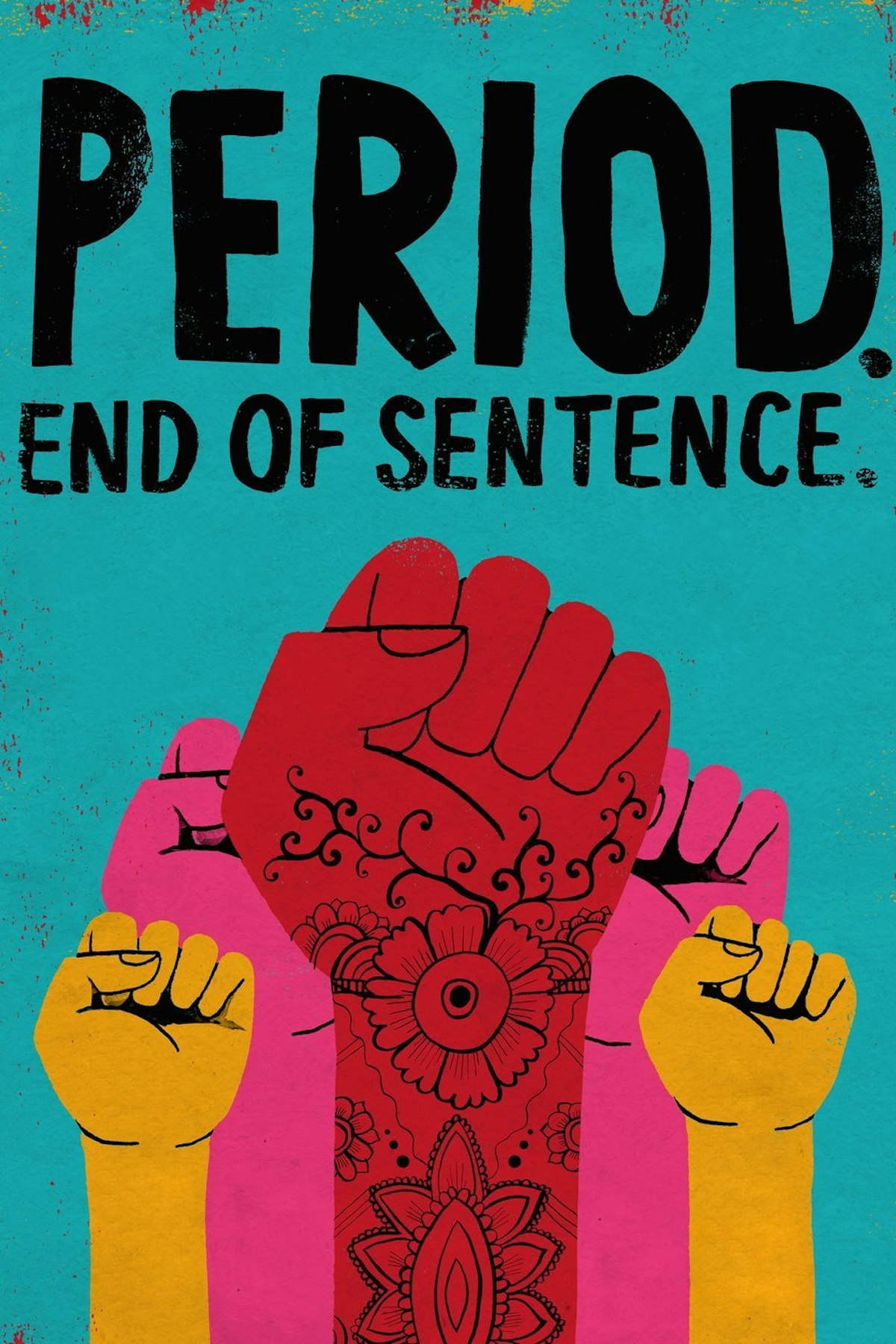

“I can’t say the word,” insists a young woman in award-winning documentary Period, End of Sentence. With brows furrowed, eyes averted, and a gaggle of young dudes snickering in the courtyard, embarrassment was written across her face. The tortuous word? “Period.”

Period, End of Sentence, a 26 minute Netflix documentary and winner of an Academy Award for Best Documentary (Short Subject), addresses menstruation stigma, telling the story of a group of women in rural Hapur, India, who install a low-cost sanitary pad machine in their village to aid in social and economic mobility. The film was directed by 25-year-old Reyka Zehtabchi, the first Iranian-American to win an Oscar, and produced by award-winning Guneet Monga, one of the “top 50 Indians changing India,” according to India Today. Period, End of Sentence follows Hapur’s women as they grow their pad brand, Fly, with the help of the pad machine.

One line from Reyka’s Zehtabchi’s Oscars acceptance speech particularly dominated Twitter feeds and film headlines:

“A period should end a sentence, not a girl’s education.”

The gender disparity between men and women in India, from literacy to income, remains sharp and the menstruation stigma only exacerbates that gap. The arrival of a period supersedes normal middle-school tampon concealing, wardrobe inconveniences, or period cup usage stress. Due to lack of access to sanitary facilities and supplies, it interrupts an education or career.

Lack of access to sanitation facilities and poor health education hinders women from a consistent work or schooling schedule while on their period. Female students and teachers, experiencing a “gender unfriendly school culture,” often miss school or go home early while on their period. Studies show that there are relatively equal levels of school enrollment and performance between boys and girls up until puberty, when they start to diverge.

One study found that 71% of girls didn’t even know about menstruation before their first period.

Sanitary supplies also prove to be expensive: 70% of women report being unable to afford sanitary pads. Without adequate sanitation supplies, some women have resorted to reusable rags, newspaper, or even dried leaves to aid absorption.

Menstruation taboos are deeply socio-religious. Various interviewees in Period, End of Sentence describe it as an illness: a curse of dirty blood from the gods, whereby women are barred from entering the temple when they are on their period. Here’s a list of off-limits activities to women on their period in certain parts of India: entering the kitchen, offering prayers, eating certain foods, taking a bath, touching a cow. While the religious rules were originally designed to protect the sacredness of religious spaces, the social stigma has since operated to restrict women’s mobility and dignity on a monthly basis.

Period, End of Sentence introduces viewers to social entrepreneur, Arunachalam Muruganantham, the inventor of the low-cost sanitary pad machine, which has since been replicated successfully in 23 out of 29 Indian states. How did social entrepreneur and high school dropout Muruganantham launch his sanitary napkin revolution? His original inspiration for the pad machine was his wife, Shanti, who he discovered using dirty rags and newspapers during her period. His wife explained to him that if she bought sanitary napkins, she would have to cut the family milk budget.

“I tried to do a small good thing for my wife. What you did in the early marriage days? You try to impress your wife. I did the same.”

When designing prototypes, Muruganantham tested the products himself, stuffing his pants with a tube filled with animal blood and wearing it while walking and bicycling, because his wife and sisters were too embarrassed to talk about the pads, much less test them. His takeaway from his voyeuristic 5-day pad-wearing experiment? “That makes me to bow down to any woman in front of me to give full respect. That five days I’ll never forget. The messy days. The lousy days. The wetness. My God it’s unbelievable!” Welcome to the club.

While older men in the village have dubbed it “the Huggie machine,” the last scene is a group of female Fly employees teaching some younger men how to make pads. “This is our timetable. We work 9-5. There’s no time for visitors to chit-chat with us.” Fly employees run a tight ship, with deft hands sorting cotton and pulling whirring machine levers. On one hand, the movie critiques long-standing patriarchal structures, but –

It also subtly recognizes that collaboration between men and women is necessary for sustainable social change.

The machine has already had a dramatic impact, as explained by director Zehtabchi: “The women were no longer ashamed. They made pads and proudly shared them with other women. They were earning their own wages and running their own business. They even invited some men to make pads.”

Fly employee Sneha, who is using her paycheck to fund her policewoman training, says of the company’s future: “I’ll be able to find Fly pads in any store.” Sneha’s primary ambition of becoming a policewoman probably didn’t factor in winning an Oscar, but everybody’s gotta have a side hustle - hers just happens to be starring in an award-winning documentary.

The result of a yoga-thon Kickstarter, a female powerhouse team, and 26 minutes on Netflix? A shiny gold Oscar statue, but more importantly, educational conversation and a sense of dignity for women in India. “The next generation is much more open,” reflects my friend Mary Elizabeth Heard, founder of a social entrepreneurship venture providing jobs for women in rural India. “I get the sense - and it’s hopeful - that things are changing.”

Photos via Flixster, BBC by Abhishek Madhukar, and Good Morning America