What began as a form of self-expression in the midst of a difficult season has since become an illustration series featuring pointedly relatable content that’s beloved by nearly a million people. In addition to her digital creations, illustrator and writer, Mari Andrew, recently published her first book, “Am I There Yet?: The Loop-de-loop, Zigzagging Journey to Adulthood”, featuring her written reflections on growing up — accompanied by her art. This new movement into the publishing world closely follows a season where Mari was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré Syndrome — a rare disease that caused her physical paralysis while abroad. I was grateful to hear from Mari about her relationship with her body following trauma and the transition back into drawing.

Talk to me about your passion for illustration; how it came to be, what defining yourself as an artist means to you, and why you fell in love with it.

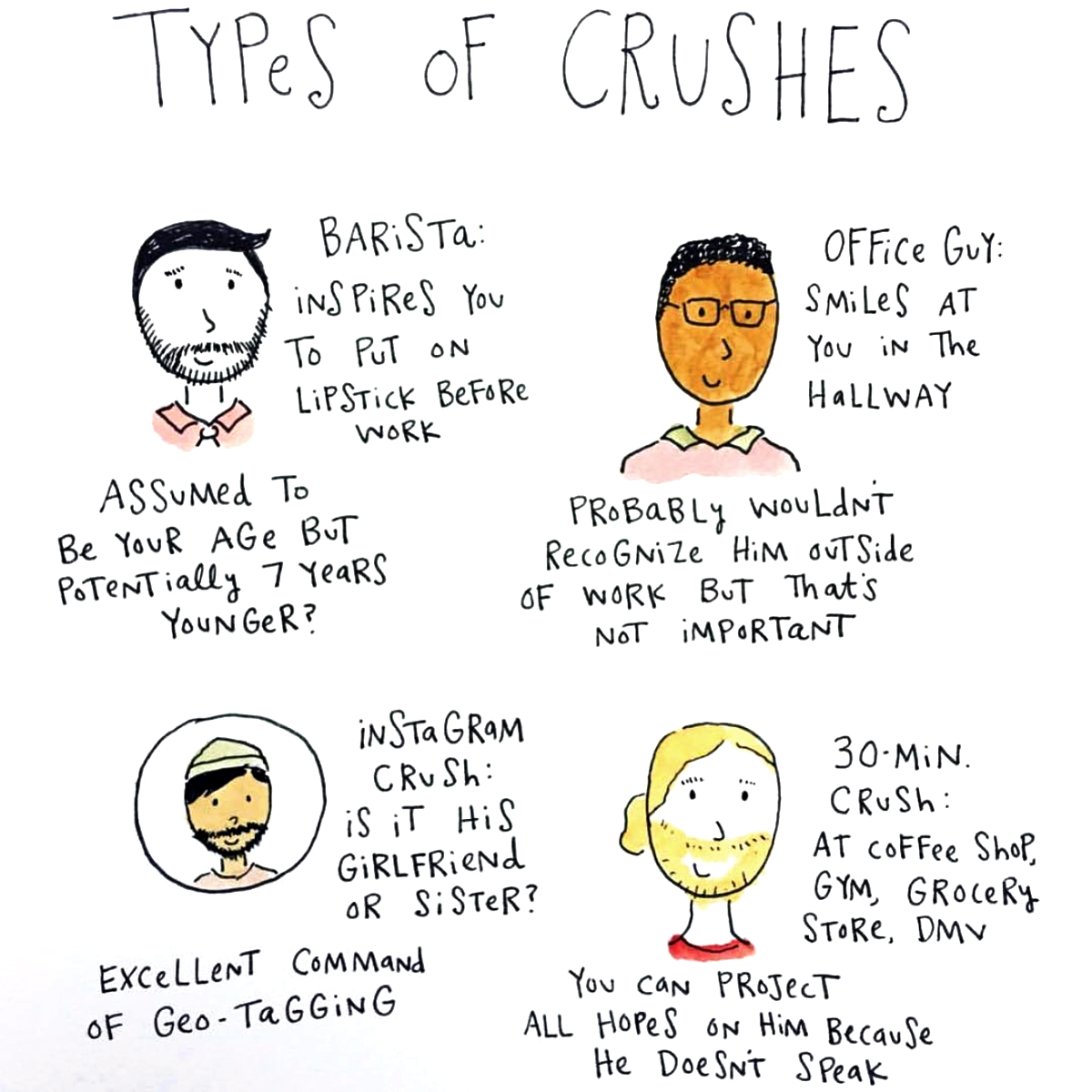

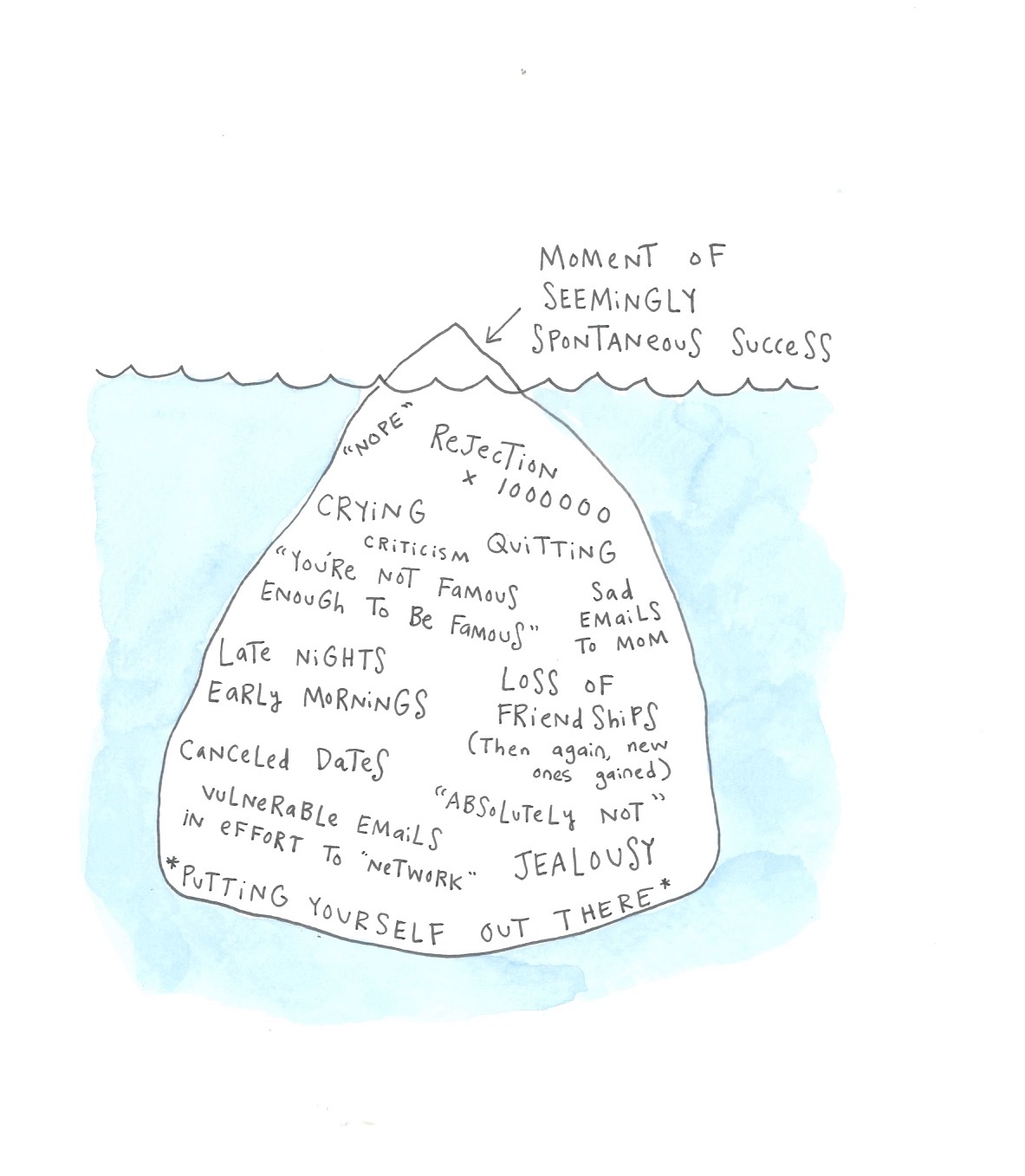

I am passionate about illustration simply because I enjoy it! I enjoy so many things: dance, good food, my friend, fashion, interior design, cheese, solo travel, writing, and languages, but illustration is the hobby I’m best known for out of all of those! I started it a bit later in life than most people; I picked up a drawing pen at age 28. I decided I wanted to do more things every day that made me happy, including drawing and using watercolors. I started an Instagram page to keep myself accountable to my new hobby, and here I am! It is still the most relaxing part of my day. Of course I was hesitant to call myself an “artist” because I have no training and I’m not very technically good at it.

I now know there is no line between “someone who draws” and “artist.” If you make any kind of art, you’re an artist–end of story.

For those that don’t know your story, tell us a bit about your time of temporary paralysis and what the reality of that situation meant for your identity as an artist. What emotions, frustrations, or struggles did that time hold?

While I was in Spain finishing my book, I was diagnosed with Guillain-Barre syndrome, an extremely rare and aggressive autoimmune disease that can paralyze your entire body. It was completely random and really came out of nowhere. Needless to say, it was terrifying to lose mobility in my legs and arms within two days.

Not only was I paralyzed, but I was in excruciating pain. It felt like someone was constantly hitting my spine with a metal rod. I’m a person who takes so much pleasure in life–in eating, drinking, having fun, talking with friends–and the pain and immobility cruelly took me away from all of that.

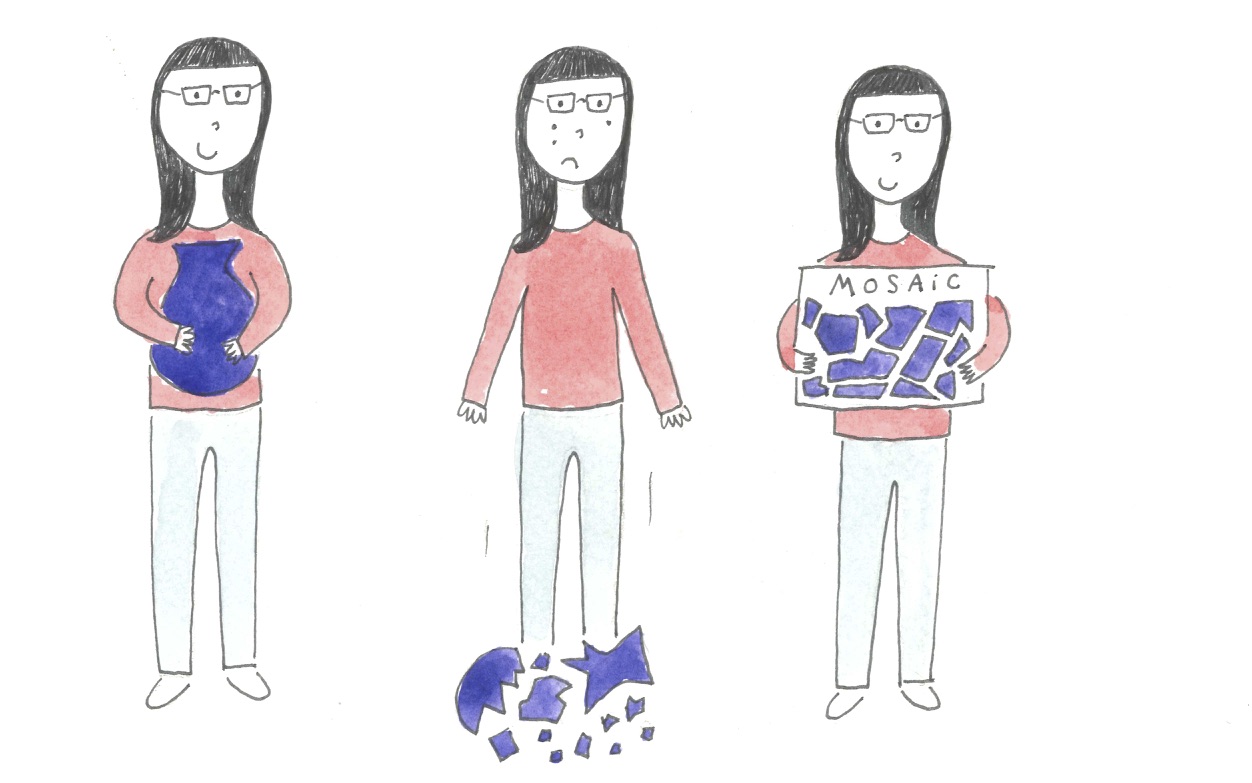

I was paralyzed for about a month, and during that time it was so frustrating not to be able to express myself through art, writing, or dance - my usual methods.

I found a new identity as “someone who is loved” rather than “someone who can do things.”

But it was so disheartening. I really got along well with a couple of my nurses, and wanted so badly to share my whole self with them–my style, my illustrations, my essays–but I had nothing to show. I was just lying there with dirty hair in a hospital gown. I felt totally useless, and ugly. Even putting on a necklace or getting my hands washed for me would make such a difference. I didn’t realize how much my identity relied on my appearance or ability to produce.

It was a horrific time of life, one in which I became intimate with the suffering that so many people live with permanently. The world is just not built for people with disabilities, and the lack of accessibility made me feel even more isolated and heartbroken during recovery.

What was the rehabilitation period like? What emotions or thoughts did it hold? How did others respond to you in the midst of it?

My rehabilitation might have been the hardest part of the whole ordeal. Similar to grief, which I have also experienced, sometimes the most difficult part comes after the really intense first month when people are still sending flowers and asking you how you are.

During recovery, my friends were just focused on how well I was doing compared to my month in the hospital. I found myself missing being in the hospital, because I didn’t have to explain myself. There, I had people rushing to help me at every moment, and daily physical and occupational therapy. Outside of the hospital, I had to fend for myself. My recovery was invisible because I looked “fine,” but I was too weak to fully participate in society. It was such a depressing and lonely time. I didn’t have the energy to do my favorite activities and it was so hard to draw, write, cook, and exercise.

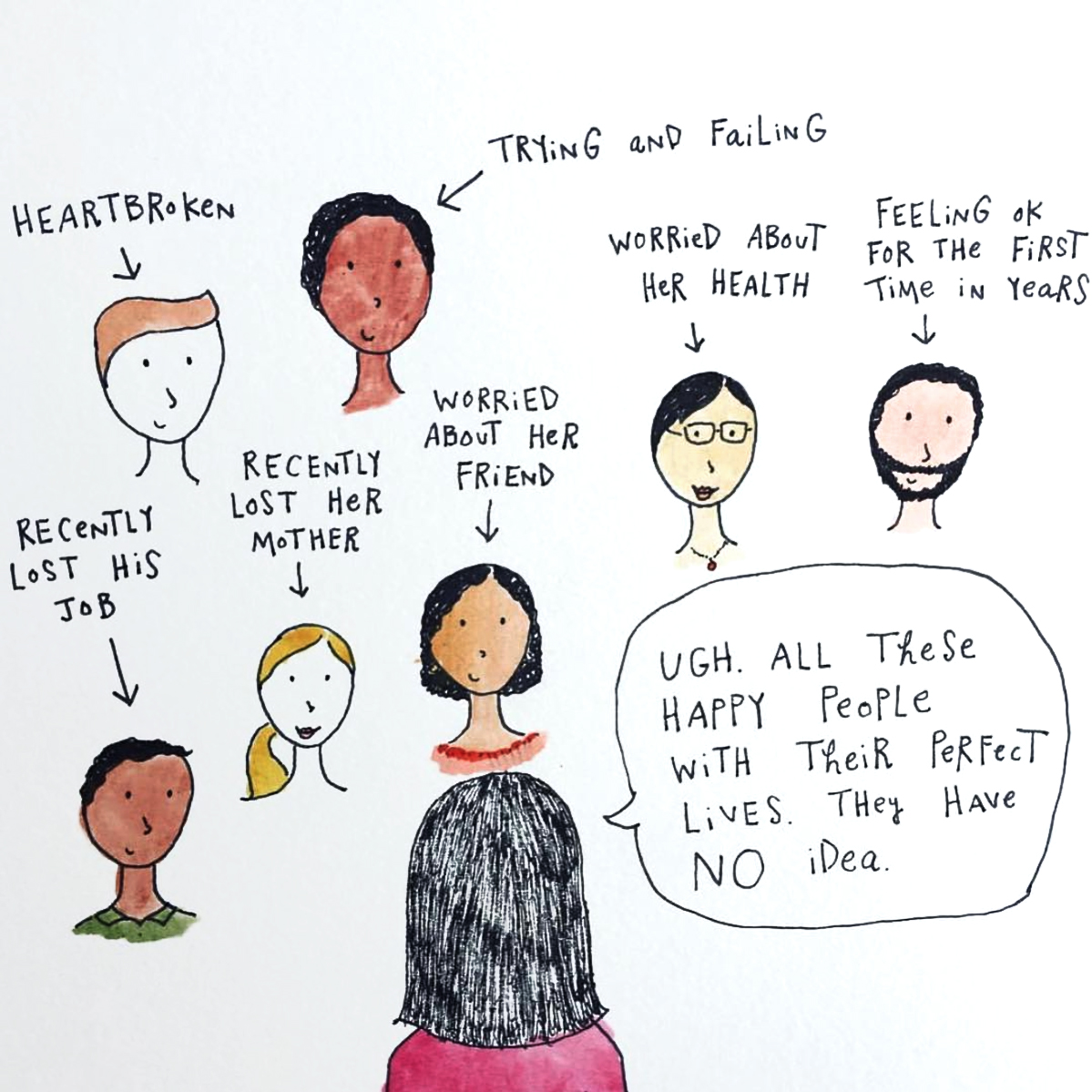

I was happy to make progress, but angry that I had to make progress in the first place. It was really frustrating learning to walk again. Everything about my recovery process was so frustrating. My friends would listen to me as best they could, but how could they really understand what I was going through? I felt like I had to put on a smiling face because I had just survived a potentially fatal disease. I ended up breaking up with my beloved boyfriend because we had a lot of communication issues that time, and I felt very strained in a lot of my friendships. I really grew to understand that good health is an enormous blessing that allows space for so much of the goodness of life.

How has your relationship with your body been throughout all this?

A dear friend wrote me a text after I was diagnosed with GBS: “I’m sure this is so hard for someone with such an exquisite relationship with her body.” I loved that. I’ve always been very active, and I take pride in my physical strength. I also process a lot of emotion through activity - long walks and once, mostly. I remember thinking, “Why would this happen to ME? I use my body more than anybody!”

I have certainly become much more grateful through this process. Every morning I write a gratitude list, and I typically begin with “grateful for mobility in my hands” or “thankful for the ability to walk” because those are not givens. For people without disabilities, it seems obvious, but it’s incredible to have the ability to move through the city with ease. I am now very sensitive to “ableist” values, such as the New Yorkers’ obsession with fast walking! I have always been a super fast walker, but now I can’t walk as fast. I hate seeing signs like “You’re in New York: Walk faster.” Some people physically cannot do that, and it’s very painful to get those messages. My empathy has increased x10000.

How have you coped with and responded to the reality of your body’s capabilities changing without your consent?

It’s traumatic. I read that the definition of trauma is anything happening to you without your consent. I feel that. I’m deeply wounded by it. I think I’ll need a lifetime of therapy to fully process it. Like any trauma, I think about it constantly. I talk about it a lot with my mom - who came to the hospital to be with me - and replay a lot of those horrible moments. It’s so hard to explain to anyone else; I’m thankful my mom was there to share a bit of it with me, because otherwise I think it would be overwhelmingly isolating. I am in therapy and will continue to go as a means of healing!

What has the transition back into drawing been like for you?

In all candor, I feel blessed that I have more experiences to express now. Before I got sick, I think I knew a lot about the human experience and some universal experiences, but health issues certainly brought up many new feelings for me.

I would never wish to go through what I went through, but I do think that it gave me a new tool to relate to people with, and a new power to heal people.

I know that empathy was such a powerful healer for me during my recovery; it was so good to hear from people who had gone through similar experiences. I hope I can be that person to someone else. It is a gift.

How can we love our bodies when they suddenly render us incapable of using them in a way we’ve identified with for so long?

What a great question. It is so hard. Everyone identifies strongly with their bodies, even if they don’t think about it that often. We either identify with our physical appearance, the way we adorn ourselves, or what we can do with our bodies. That includes knitting, hugging, weight-lifting, letter-writing, or picking up our pet cat.

Being disconnected with my body was an experience that really wounded me. However, I knew that I had to take very gentle care of myself, the way I’ve been doing for years. It was my priority to do things that felt really good. Many people suggested acupuncture to me, but I didn’t really enjoy that experience. Instead, I got a ton of massages. I was told that massages wouldn’t help me, but it just felt good and made me feel a lot better. Therefore, it was healing.

I also had to think outside the box. I’ve always been a dancer, but I couldn’t point my toes anymore! So, I decided to take African-based dances, which are mostly done with flat feet. I signed up for Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Brazilian, and West African dance classes. It was a way that I could reconnect with myself in a pretty low-stakes way. I wasn’t trying to get back to my old routine (that would depress me); I was making a brand new one. Who cares if I didn’t master Afro-Caribbean moves right away? I was totally new to it. I think trying a new thing during recovery is the key to building up confidence and curiosity again.

Images courtesy of Mari Andrew

CONNECT WITH CREATIVE, PURPOSE DRIVEN ENTREPRENEURS: BECOME A YELLOW MEMBER